after what age does a woman’s ability to conceive begin to decline?

- Inquiry commodity

- Open Access

- Published:

Determinants of change in fertility pattern amidst women in Uganda during the period 2006–2011

Fertility Inquiry and Exercise volume iv, Article number:4 (2018) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Groundwork

Studies on fertility in Republic of uganda have attributed fertility reduction to a shift in the overall characteristics of women of reproductive age. It is not clear whether the reduction in fertility is due to changing socioeconomic and demographic characteristics over time or stems from the shifts in the reproductive behavior of women. In this paper nosotros examine how fertility rates have changed between 2006 and 2011 and whether these changes take resulted from irresolute characteristics or from changing reproductive behavior of women.

Methods

Using the 2006 and 2011 Demographic and Wellness Survey information for Republic of uganda, Multivariate Poisson Decomposition techniques were applied to evaluate observed changes in fertility.

Results

Changing characteristics of women aged xv–49 years significantly contributed to the overall alter in fertility from 2006 to 2011. The alter observed in older historic period at showtime marriage was the major correspondent to the changes in fertility. The contribution that tin be attributed to changes in reproductive behavior was non significant.

Conclusions

This report finds that the major contribution to the reduction in fertility betwixt 2006 and 2011 was from increased education and delayed marriage amid women. Continued comeback in secondary schoolhouse completion, will lead to older historic period at showtime matrimony and will go on to be an of import factor in Uganda's declining fertility rates.

Background

Full fertility rate (TFR), the number of alive births that a adult female would take at the finish of her reproductive years if the prevailing age specific fertility rates remained constant [1] has declined in all developing regions of the world. In Asia and Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa, a decline in TFR began in the mid-1970s, and 1990s respectively [2]. Whereas Asia and Latin America have had rapid fertility declines, the declines in Africa and particularly Sub-Saharan Africa take been small-scale [three]. For example between 1950 and 2010, total fertility rates (TFR) in Asia and Latin America declined from 5.eight and five.ix children per woman respectively to most 2.3 children per woman, while Africa's fertility declined from six.6 to 4.9 children per adult female in the same period [iv]. Kabagenyi, et al. [five] examined the onset of fertility transition in Uganda only constitute no bear witness of a stall. They indicated that Uganda'southward TFR declined for a flow of time and so remained constant. The TFR ranged between 8 in 1970s to six in 2010. Current population census results in Uganda bespeak that between 2002 and 2014, TFR declined from 7.0 children per woman to 5.8 children per woman [vi]. Even so, the TFR of 5.eight children per woman was the tenth highest in the world [seven].

Studies have constitute fertility changes to exist associated with changes in demographic, socioeconomic and cultural factors which particularly influence family unit size, contraceptive access and utilize and age at get-go wedlock [viii,9,x]. Changes in fertility ascend from irresolute characteristics of women as well equally changing reproductive beliefs that occur as a result of changing characteristics [9]. The changing characteristics of women and changing reproductive behavior tin have varying influences on fertility. For case, Rutayisire, et al., [9] found that a subtract in the proportion of women who were currently in unions (marriage and cohabitation) contributed much to lowering Rwanda's fertility between 1992 and 2000. On the other hand, changing reproductive behavior revealed that the fertility of the women in unions was higher in 2000 compared to 1992. The subtract in the proportion of women in unions was more than commencement by the shift in their reproductive behaviors and thus fertility remained higher [9].

Uganda'due south persistently high fertility has been attributed to depression levels of contraception amongst women [11]. Previous studies in Uganda have documented differential changes in fertility among population sub groups. For example faster refuse is shown amongst the most educated women; these reside in urban areas and specific regions of the state [12, thirteen]. These studies accept highlighted the influence of women's social, economic and demographic factors in fertility change. The studies however have non isolated the modify in fertility that is owing to changing characteristics of women over time from that which is due to the changing reproductive behavior.

Changing characteristics refer to changes in proportion of the population with particular social, economic and demographic characteristics, while the change in reproductive behavior refers to the changes in the behavior of the population as a event of the change in characteristics [14]. In this study nosotros used number of children always born (CEB) every bit the measure out fertility to conduct a decomposition assay of modify in fertility in Uganda between 2006 and 2011. The CEB measures the number of children built-in to a woman reported upward to the moment at which the data are nerveless [1]. Specifically, this study determines variations in fertility between 2006 and 2011 that tin can be attributed to changing characteristics of women aged xv–49 years and assesses the variations that can be attributed to changes in reproductive behaviors of the women anile 15–49 years.

Methods

Information obtained from the Republic of uganda Demographic and Health Surveys (UDHS) conducted in 2006 and 2011 were used. Surveys were conducted by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics. The surveys were nationally representative cross sectional surveys that collected comparable demographic and health information on women anile 15–49 in the survey periods. The samples were obtained using a two-phase cluster sampling process beginning with the pick of clusters, or enumeration areas, followed by the selection of households from each cluster [xv]. Since this study used secondary information, research approval from the Institutional Review Lath was not applicable. The DHS data is freely available and the public tin can access information technology upon a formal request. We submitted an abstract to Mensurate DHS seeking permission to utilise the data and the required access was subsequently permitted.

This study is based on the secondary analysis of data of women aged xv–49 years collected in the 2006 and 2011 demographic and health surveys. The women anile fifteen–49 years in both the 2006 and 2011 surveys were asked almost their birth histories and this provided information on the full number of children e'er built-in. Since we were interested in determining the factors that may explicate variations in fertility between 2006 and 2011, we adopted a multivariate decomposition assay. Multivariate decomposition analysis is used to quantify changes over time into components attributable to changing characteristics and changes in reproductive behavior [14]. We used CEB equally the measure out of fertility.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Women who had always had sex were included since they were the only ones with the potential for pregnancy and child nascency. In the DHS, women were asked "how onetime were you when you had sexual intercourse for the very first time?" This question was about the sexual activeness of women. It is all the same possible that there was underreporting and misreporting, as the question may exist sensitive to young women and especially unmarried adolescents who might non feel comfortable to disembalm information related to sexual activities. It is thus possible that some women who had sexual activity only did not declare so were excluded.

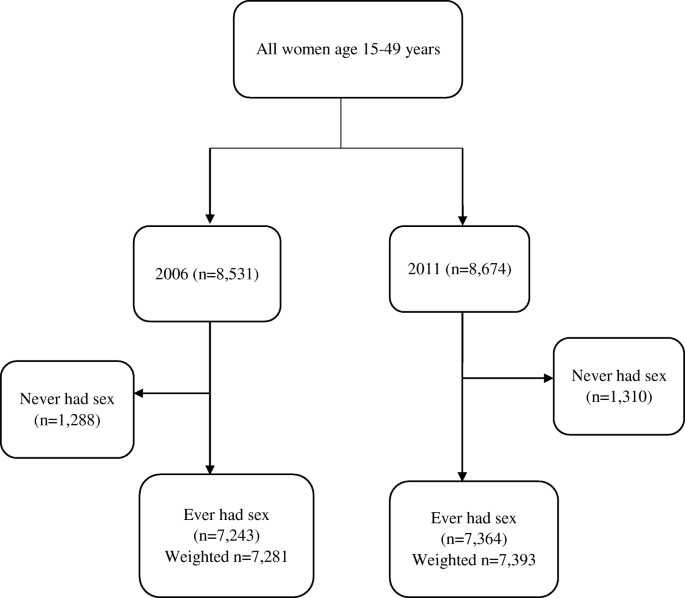

From a total of 8531 and 8674 women aged fifteen–49 years interviewed in the 2006 and 2011 UDHS respectively, we selected a full of 7243 and 7364 women aged xv–49 years who reported having ever had sex activity in the respective surveys. The weighted sample was 7281 women and 7393 women in 2006 and 2011 respectively. Figure one below is a flow chart that shows how the sample was derived.

Derivation of the study sample

Variables

The dependent variable used in the report was the number of children ever born (CEB) to a female respondent in the 2 surveys. The independent variables were; age (current age of respondent in 5-yr groups), education (highest education level attained by the respondent), residence (type of place of residence of respondent), faith (faith of respondent), wealth quintile (household wealth index), sexual practice of household head (sex of the head of the household), polygamy (whether the respondent is in a polygamous marriage or was aware of other co-wives), working condition of women (whether the respondent is currently working or not), exposure to family planning messages (whether respondent heard about FP on radio, TV and newspaper or non), knowledge most contraceptives (whether respondent has knowledge of any family planning method or not), source of contraceptive (the concluding source of modern family planning methods for users or respondent is non-user), historic period at showtime sex (historic period of the respondent at first sexual intercourse), platonic family size (Platonic number of children the respondent would take liked to take irrespective of number she already has), contraceptive use (electric current use of any contraceptive method), age at showtime marriage (age at kickoff start of marriage or matrimony. Due to the tendency to give birth earlier marriage, we introduced the "not yet married" category). These independent variables have furnishings on the outcome in two ways: the distribution result (changes in characteristics of women) and the behavior effect (this is shown by regression coefficients of the variables on the outcome. For example, modify in fertility may be due to differences in distribution of women past instruction level attainment and also due to the effects of education on the reproductive beliefs. Assuming women with higher education have a lower CEB, a decrease in TFR may exist observed if more women in 2011 had a higher level of educational activity when compared to women in 2006. This is an case of how irresolute characteristics can influence the TFR. In addition, women achieving a higher level of didactics may purposefully decrease the number of CEB, which would also lead to a subtract in TFR. Therefore changing reproductive behavior tin influence the TFR.

Information assay

Using the 2006 and 2011 DHS data sets for Uganda, a Poisson regression offset by the natural logarithm of the current age of women was done for each survey period to determine the factors associated with number of children ever born. The data were starting time weighted to ensure representativeness of the sampled data. A weighting variable generated using the sample weight variable in the DHS data was practical in all statistical commands. This variable was used in all the models. The weighting took into account the complex sample design used in the DHS. The coefficients were exponentiated to yield incident charge per unit ratio (IRR) to ease interpretation of the results. The incident rate ratio explains how changes in X (independent variable) affects the rate at which Y (CEB) occurs.

$$ \mathrm{In}\left({\mu}_i\right)=a+{X}_i{\beta}_i+\mathrm{In}(age) $$

(1)

where, μ i is the expected number of children born to a respondent based on the respondent's demographic and socioeconomic characteristics; X i are independent variables; α is a abiding and β i represents coefficients associated with the independent variables. ln(age), is the offset variable. This offset variable was generated from the variable age. In addition, nosotros adjusted for marital status since marital status significantly related to the number of children ever born, as married or formerly married women are more likely to have more children e'er born than the never marrieds. To know whether there was a significant change in number of children ever built-in between the two survey years, a i-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) which reports hateful number of children ever built-in (MCEB) was used.

To make up one's mind the factors associated with the change in fertility between 2006 and 2011, a multivariate Poisson decomposition model was used to partition change in mean number of children ever born into components attributable to changing characteristics of women and that due to irresolute reproductive behavior of the women. The technique also partitions the two components into portions that correspond the unique contribution of each predictor to each of the two components in a detailed decomposition (Powers, Yoshioka, & Yun, 2011). The general decomposition equation is as beneath:

$$ \overline{Y_B}-\overline{Y_A}=\overline{F\left({X}_A{\beta}_A\right)}-\overline{F\left({Ten}_B{\beta}_B\right)} $$

(2)

The eq. ii can be further decomposed to eq. iii below

$$ \overline{Y_B}-\overline{Y_A}=\left\{\overline{F\left({X}_A{\beta}_A\correct)}-\overline{F\left({Ten}_B{\beta}_A\right)}\right\}+\left\{\overline{F\left({Ten}_B{\beta}_A\right)}-\overline{F\left({X}_B{\beta}_B\right)}\right\} $$

(3)

The summarized grade of eq. three is every bit in eq. iv

$$ \overline{Y_B}-\overline{Y_A}=Eastward+C $$

(4)

where; \( \overline{Y_B}-\overline{Y_A} \) is the Mean deviation in children e'er born between Twelvemonth B (2011) and year A (2006), F(·) is a logarithmic function mapping a linear combination of X (Xβ) to Y, Ten represents predictors and β represents regression coefficients. The summarized component Eastward refers to the role of the alter attributable to changing characteristics while the C component refers to the part of the change attributable to irresolute reproductive behavior. The Year 2011 is the comparison group and year 2006 is the reference group. Due east reflects the expected difference if Twelvemonth 2011 were given Year 2006'south distribution of covariates. C reflects the expected difference if Yr 2011 experienced Year 2006's behavioral responses to X.

The results of the multivariate decomposition were interpreted using the coefficients on the two components. Specifically, a positive characteristics coefficient indicates the expected reduction in the fertility gap if the women in 2011 had the same distribution of characteristics of women in 2006. The fertility gap is means the change in number of children ever born. On the other hand, a negative behavioral result coefficient indicates the expected increment in the fertility gap if women in the 2011 survey were given the coefficients of the 2006 survey. The overall per centum contribution of a characteristic to the gap in fertility is obtained by summing the percentages for the various categories of the characteristic. All the statistical significances of associations were determined at the 0.05 level of significance.

Results

Nosotros studied a total weighted sample of xiv,674 women anile 15–49 years, 49.half dozen% of whom were from the 2006 survey and l.4% from the 2011 survey. Our results indicate significant differences in characteristics that include age, education level, organized religion, electric current working status, polygamy and exposure to family planning messages (p < 0.05). Other characteristics that impacted CEB were source of modern family planning methods, knowledge of any family planning methods, contraceptive use, historic period at starting time sex, family unit size preference and age at kickoff marriage. The characteristics of women and the associated difference in proportions in 2006 and 2011 are presented in Tabular array 1.

Between 2006 and 2011, in that location was a significant difference (p = 0.004) in the percentage of women by age. Specifically, the percentage changes in the women anile 15–nineteen, 20–24, 25–29, thirty–34, 35–39, xl–44 and 45–49 were; 1.i, − one.5, one.8, − 2.1, 1.0, − 0.2 and 0.1 respectively. The per centum of women who had non attained whatever level of education decreased past 7.4%, while the proportion of women who had attained at to the lowest degree a secondary level of didactics increased by 6.8%. Similarly, the percentage of women living in urban areas increased past 3.3%. Regarding wealth quintile, there was slight reduction in the proportion of women in the poorest, poorer, and middle categories and a slight increase in proportion of women in the richer and richest categories. The results also indicate that the proportion of women in the "not working" category increased by eleven.5%. There was a reduction of 2.5% in the proportion of women who were in a polygamous spousal relationship.

The proportion of women reached by family planning messages increased by 4.half dozen% in the period 2006–2011. Similarly, the proportion of women who reported getting modernistic family planning methods from the government facilities increased past 5%. There was a notable change in contraceptive use. The proportion of women who were currently using any contraceptive increased by 4.viii% between the ii survey periods. The findings further indicate that the proportion of women whose sexual debut was below the historic period of xx years reduced by 12% signifying an increment in the age at sexual debut among women aged xv–49 years in 2011. Relatedly, at that place was a three.7% reduction in the percentage of women marrying before the historic period of 20. The proportion of women who desired at least v children reduced by four% and those who desired three–iv children increased by 3.7%.

Changes in fertility

Changes in fertility in this study are described by changes in number of children ever born (CEB) to the women. A computation of the mean number of children always born (MCEB) was done using oneway ANOVA. The results revealed that the MCEB was 4.1 in 2006 and three.9 in 2011 and that there was a statistically significant difference in MCEB between 2006 and 2011 (p = 0.000) at the 95% confidence level.

A Poisson regression get-go by the natural logarithm of the current age of women was done for each survey period to find out the factors associated with CEB. Table two reveals that in both 2006 and 2011, the women who had attained at to the lowest degree a secondary level of education had a lower MCEB compared with their counterparts. Relatedly, in both 2006 and 2011, there was generally higher fertility among rural women compared to their urban counterparts. The results also indicate that women in the richest wealth quintile had a lower fertility. Female headed households had lower MCEB compared with the male person headed households and for the two surveys, currently working women had higher fertility. Women who were in polygamous marriage in both 2006 and 2011 had higher MCEB compared with their counterparts who were not. When adjusted for age and marital status, the working status and co-wife status significantly affected number of children always born only in 2006.

After adjusting for age and marital status, women who knew whatsoever family unit planning methods in 2006 were found to have higher fertility compared with their counterparts who did not have any noesis. Furthermore, women who were currently using a contraceptive method had higher fertility compared to those who were not. However, when adjusted for age and marital status, the influence of contraceptive use was non significant for the ii surveys. In both 2006 and 2011, the MCEB was lower among women whose historic period at showtime sex activity was reported to be at to the lowest degree 20 years. Relatedly, the results indicate that in both 2006 and 2011, fertility was lower amid women whose age at first marriage was xx years or older. When adjusted for age and marital status; education, place of residence, wealth quintile, sex of household head, age at start sex and family size preference remained significant while contraceptive use was not significant. Table ii shows both the crude and adapted results.

Decomposition of fertility alter

Table iii shows the overall contribution of characteristics and reproductive behavior of the women on the observed variation in number of children ever born. The findings indicate that the overall change in fertility between 2006 and 2011 was attributed to changing characteristics of women. Changing reproductive beliefs did not contribute significantly to the observed change in fertility.

Results of the detailed decomposition presented in Table 4 reveal that the change in fertility was due to changes in age, education level, place of residence, wealth quintile, polygyny, household headship, exposure to family unit planning messages, contraceptive use, age at first sex, family size preference and age at first marriage.

The significant variables in the model (age, education level, identify of residence, wealth index, sex of household caput, polygyny, exposure to family planning messages, contraceptive use, age at outset sex, family unit size preferences and historic period at beginning union) were tested for confounding. Age was found to exist a confounder in the model. The findings indicated that when historic period was dropped from the model, education was the biggest contributor with 47.eight%, followed by age at showtime spousal relationship (forty.9%), women's preferred number of children (29.7%), working status (23.8%), contraceptive use (19.8%), exposure to family unit planning letters (12.vii%), identify of residence (eleven.i%), age at first sex activity (8.7%) and polygyny (three.iv%).

Discussion

Our analysis reveals that of characteristics and reproductive behavior, just changing characteristics of women significantly contributed to the observed change in number of CEB built-in between 2006 and 2011. The study results highlight importance of change in women's educational attainment and age at first spousal relationship to fertility. With an increase in the proportion of women who have attained at least a secondary level of education, this study highlights significant declines in fertility. The nationwide implementation of the Universal Secondary Education Policy in 2007 increased the proportion of women who attained at least secondary level of education in 2011. The increased attainment of college level of education could have delayed entry into marriage and too increased the likelihood of using contraceptive methods. This confirms the notion that improvements in education of women is instrumental in fertility decline. Bagavos and Tragaki [sixteen]; Westoff, Bietsch and Koffman [x] besides as Shakya and Gubhaju [17] too observed that increasing women's educational attainment is a key factor contributing to sustained fertility decline. Still, this finding partly disagrees with Cai [18] who in a study conducted in Cathay found that improvement in education had no effect on fertility change. This may partly exist due to socioeconomic context differences between Republic of uganda and Prc as well as the different policies that be in the two countries. In China, the strong government intervention in birth command policy could have suppressed variation in fertility. This is not the example for Uganda since the number of children is largely a personal choice and this tin can partly explain why didactics is such a significant contributor to changes in Uganda'due south fertility. Our findings as well point to the need for mechanisms to increase the age at which women marry. The results are in line with other studies that contended that an increase in age at first marriage reduces fertility [5, 19, 20]. This finding also concurs with Beatty [one] who contended that fertility transition is not likely to begin in a state where age at kickoff spousal relationship for women is still low.

An increase in the proportion of women that were exposed to family planning messages between 2006 and 2011 was institute to have contributed to the variation in fertility during the period. The finding suggests that if the population experienced increased exposure to family planning messages, a fertility transition can be facilitated. Exposure to family planning messages may atomic number 82 to changes in attitudes towards large families and use of contraceptive methods which in turn atomic number 82 to adoption of pocket-size family unit norms such as contraceptive use. Appropriate mass media campaigns on family planning should target high fertility areas rural areas. The importance of exposure to mass media has been reported to be a determinant of the number of children desired and increased use of modern contraceptives [8, 10, 21]. Although contraceptive utilize amid women in Uganda was still depression, our findings indicated that contraceptive employ contributed significantly to the change in number of children e'er born. This finding points to the demand for continued and increased authorities and international support for quality family planning if sustainable fertility reduction is to be achieved. This finding confirms what numerous studies take asserted about contraceptive use significantly driving fertility transition [9, 12, 17, nineteen, xx, 23]. However one report conducted in Uganda reported that modern contraceptive use did not influence the country'due south fertility rates [five]. This may be because the study by Kabagenyi et al. looked at contraceptive use for one survey period but did not encompass the time variations in the effects of contraceptive use.

The contribution of family size preference to the observed alter in fertility tin exist linked to the reduction in the proportion of women desiring large family size (at to the lowest degree five children). Family unit size preferences bear on people'due south fertility behaviors and especially decisions on whether to utilise or non to use contraceptives. In that location is need to go on reaching the population specially in rural areas with information almost the benefits of smaller families. The importance of shift in desired family unit size in fertility decline was confirmed in diverse studies [8, 10, 12, 22, 23]. In fact an earlier study asserted that fertility desires and not contraceptive access matter in fertility change [19].

This written report too found that increase in the proportion of women who delayed their sexual intercourse to at to the lowest degree 20 years influenced the observed variation in children ever born. Delayed sexual intercourse implies delayed exposure to pregnancy and childbearing. Government and other stakeholders such as parents, local leaders, and religious leaders should keep encouraging immature people to delay entry into sex. Most of the sexual abstinence messages in Republic of uganda have focused on the prevention of sexually transmitted infections and especially the Human Immune-deficiency Virus (HIV), it is thus important that such messages incorporate pregnancy and childbearing.

The increases in the proportion of women residing in urban areas significantly influenced the 2006–2011 observed change in fertility. This may be due to improved access to family planning services and data, education and existence of smaller family size norms that usually characterize urban areas. This finding resonates with other studies that have found faster change in fertility among women residing in urban areas compared to rural counterparts [5, 10, 12, 17, xx]. Relatedly, the findings take indicated that if household wealth improved, fertility decline. The government of Uganda initiated the "Operation wealth creation" which if well implemented presents an opportunity for the land to achieve faster fertility decline particularly in the rural areas where they are based. Dribe, Hacker and Scalone [24] support this as they contended that centre classes and the rich grade experience faster fertility transition compared to the poor.

Although the time period for this assay is very brusk for detailed explanation of demographic transitions which are known to take longer periods, the two survey years chosen, 2006 and 2011 represented a flow in which visible change in fertility was reported. The 2006 and 2011 Uganda Demographic and Wellness Survey reports indicated that the fertility rate in Uganda reduced from 6.7 children per woman in 2006 to 6.2 children per woman in 2011 [15]. Earlier surveys had indicated that fertility had persisted merely over half-dozen.7 children per woman. The written report intended to identify the factors that contributed to the observed modify in fertility between 2006 and 2011.

In our analysis, we but included women who had e'er had sexual activity. Most studies on fertility focus on married and ever married women or all women of reproductive age. By focusing on e'er married and married women, such analyses exclude not-marital and premarital fertility which are seemingly increasing in recent times. The current study focused on women who had ever had sex so that merely women exposed to the risk of pregnancy and childbirth are included in the analysis. Nonetheless, this inclusion criteria may correspond a limitation of the written report as in that location may have been under reporting or even refusal to report on sexual activities especially among adolescents who may fear to disclose freely disembalm their sexual histories. In most cultures, unmarried young people are expected to abstain from sexual intercourse and thus such young people who are non married may decline to disclose their sexual action status.

In that location is a possibility that some women who were and interviewed in the 2006 survey were once more interviewed in 2011. Even if some women were interviewed both in 2006 and 2011, at that place could accept been changes in characteristics too as reproductive behavior. For example, a woman who was interviewed as a non-user of family planning in 2006 could have been interviewed as a "user" in 2011. Relatedly, a woman who was interviewed anile twenty years and who had not notwithstanding given nativity in 2006 was aged 25 years in 2011 and could have fifty-fifty given birth.

At that place may exist rural and urban disparities in the importance of the factors explored by this written report. We propose that future studies explore the determinants of alter in the rural and urban areas separately in gild to understand the factors influencing fertility change in the 2 areas.

The strength of this manuscript is that the analysis is based on survey data which is nationally representative. The analysis technique used facilitates the portioning of change in an outcome over time into components attributable to irresolute socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of women and irresolute reproductive behaviors.

Decision

The decomposition technique quantified the contribution of irresolute characteristics and changing reproductive behavior of the women to the observed change in fertility design among women in 2006 and 2011. The cardinal contributors to the alter in fertility were; changes in age at first marriage, age of women, education level attained, platonic number of children, exposure to family planning letters, age at sexual debut, identify of residence, wealth index and contraceptive use.

As Republic of uganda continues to focus on harnessing its demographic dividend resulting from changes in the age structure of the population emanating from rapid fertility decline, it is important that the authorities continues its support for investments in didactics and wealth creation programs. The findings bespeak to the demand for regime and its partners to increment the number of family planning service points and intensified outreaches focusing on fertility command. Increasing support for family planning activities and specially efforts to ensure increased availability and accessibility of quality family planning methods and the intensification of mass media campaign efforts to provide messages on the benefits of family planning and fertility limitation will not only contribute to utilization of contraceptives but would also lead to changes in attitudes towards large families.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

analysis of variance

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CEB:

-

Children always born

- DHS:

-

Demographic and Health Survey

- IRR:

-

Incident Charge per unit Ratio

- MCEB:

-

Mean Children E'er Born

- TFR:

-

Total Fertility Rates

- UBOS:

-

Uganda Bureau of Statistics

- UDHS:

-

Uganda Demographic and Wellness Survey

References

-

Swanson, David A. and Chiliad.Edward Stephan. 2004. "Glossary." Pp. 751–78 in The methods and materials of demography, edited by J. South. Siegel and D. A. Swanson. San Diego, California, USA: Elsevier Academic Printing.

-

Beatty A. The determinants of recent trends in fertility in sub-Saharan Africa: Workshop Summary. edited by Partitioning of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2016. Retrieved https://www.nap.edu/21857.

-

United Nations. World fertility patterns 2015. New York; 2015.

-

United Nations. Fertility levels and trends as assessed in the 2012 revision of world population prospects. In: New York; 2013.

-

Kabagenyi, Allen, Alice Reid, Gideon Rutaremwa, Lynn M. Atuyambe, and James P. K. Ntozi. 2015. "Has Republic of uganda experienced any stalled fertility transitions? Reflecting on the last iv decades (1973–2011)." Fertility Research and Practice i(1):14. Retrieved (http://fertilityresearchandpractice.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40738-015-0006-1).

-

UBOS. The National Population and Housing Demography 2014– Main Report. Republic of uganda: Kampala; 2016.

-

Population Reference Bureau. 2016. 2016 Globe Population Information Sheet with a Special Focus on Human Needs. Washington, DC 20009 USA. Retrieved https://assets.prb.org/pdf16/prb-wpds2016-spider web-2016.pdf.

-

Ramsay S. Realising the demographic dividend. In: A Comparative Analysis of Ethiopia and Uganda. Germany: Bonn and Eschborn; 2014.

-

Rutayisire, Pierre Claver, Pieter Hooimeijer, and Annelet Broekhuis. 2014. "Changes in fertility pass up in Rwanda : a decomposition assay." International Periodical of Population Research 2014:ane–xi. Retrieved (http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/486210).

-

Westoff CF, Bietsch K, Koffman D. Indicators of trends in fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. Maryland, U.s.a.: Calverton; 2013.

-

Haub C, James K. The earth at 7 billion. Washington DC.; 2011. Retrieved (https://www.prb.org/webinar-2011-wpds/).

-

Ezeh AC, Mberu BU, Emina JO. Stall in fertility decline in eastern African countries: regional analysis of patterns, determinants and implications. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2009;364:2991–3007.

-

Lubaale, Yovani Adulamu Moses, J. B. Kayizzi, and G. Rutaremwa. 2007. "Fertility decline in urban Republic of uganda: a strategy for managing fertility in rural areas." Makerere University Research Journal two(two):51–59.

-

Powers DA, Yoshioka H, Yun Thou-Southward. Mvdcmp: multivariate decomposition for nonlinear response models. Stata J. 2011;11(4):556–76.

-

UBOS and ICF International Inc. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Kampala, Uganda: UBOS and Calverton, Maryland: ICF International Inc.; 2012.

-

Bagavos, Christos and Alexandra Tragiki. 2017. "The compositional effects of education and employment on Greek male and female fertility rates during 2000 – 2014." Demogr Res 36(47):1–20. Retrieved http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol36/47/.

-

Shakya K, Gubhaju B. Factors contributing to fertility turn down in Nepal. J Population Soc Studies. 2016;24(1):13–29.

-

Cai Y. China'south below-replacement Fertility: government policy or socioeconomic Evolution? Popul Dev Rev. 2010;36(September):419–40.

-

Bongaarts, John. 2006. "The causes of stalling fertility transitions." Stud Fam Plan 37(1):i–16.

-

Garenne, M. Michel. 2008. Fertility Changes in Sub-Saharan Africa. Calverton, Maryland, USA.

-

Grimm K, Sparrow R, Tasciotti Fifty. Does electrification spur the fertility transition? Bear witness from Indonesia. Census. 2015;52(5):1773–96.

-

Lyager, Marie. 2010. Fertility refuse and its causes. An Interactive Analysis of the Cases of Uganda and Thailand.

-

Westoff CF, Anne RC. The Stall in the Fertility Transition in Republic of kenya. Calverton: ORC Macro, MEASURE DHS; 2006.

-

Dribe Thousand, David Hacker J, Scalone F. Socioeconomic status and net fertility during the fertility reject: a comparative analysis of Canada, Iceland, Sweden, Kingdom of norway and the U.s.. Popul Stud (Camb). 2015;68(2):135–49.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mensurate DHS for granting permission to apply the UDHS information and Prof. Daniel A. Powers for developing the decomposition command used in the analysis as well as providing technical support in the initial stages of the manuscript. The try of the Reviewers is appreciated.

Availability of supporting data

The DHS data is freely available for access by the public through Measure DHS website. https://dhsprogram.com/information/bachelor-datasets.cfm

Writer data

Affiliations

Contributions

PA conceived, designed and implemented the written report inclusive of data analysis, interpretation of results, discussion and manuscript drafting. AK provided guidance in the conceptualization, data assay, interpretation of results and manuscript evolution. AK too reviewed the scientific content of the report. AN guided on the conceptualization, brash on data analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors' information

Paulino Ariho is a Graduate of Demography from the Department of Population Studies, Makerere University. He lectures in the Section of Folklore and Social Administration, Kyambogo University. Allen Kabagenyi (PhD) and Abel Nzabona (PhD) are demographers researching into population issues and lecturing at the Section of Population Studies, Schoolhouse of Statistics and Planning, Makerere University.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Permission and access to the dataset was granted past Measure out DHS.

Consent for publication

Not applicative.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they accept no competing interests.

Publisher's Annotation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This commodity is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution iv.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give advisable credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Artistic Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data fabricated available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Most this commodity

Cite this article

Ariho, P., Kabagenyi, A. & Nzabona, A. Determinants of change in fertility blueprint among women in Republic of uganda during the period 2006–2011. Fertil Res and Pract 4, 4 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40738-018-0049-ane

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40738-018-0049-1

Keywords

- Change in fertility

- Children ever-born

- Decomposition

- Socioeconomic factors

- Demographic factors

- Uganda

Source: https://fertilityresearchandpractice.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40738-018-0049-1

0 Response to "after what age does a woman’s ability to conceive begin to decline?"

Post a Comment