The Samurai in Feudal Japan Were Similar to What Social Class in Feudal Europe?

Feudalism in medieval Japan (1185-1603 CE) describes the relationship between lords and vassals where country ownership and its use was exchanged for military service and loyalty. Although present earlier to some degree, the feudal arrangement in Japan was really established from the beginning of the Kamakura Period in the late 12th century CE when shoguns or armed forces dictators replaced the emperor and royal court as the country'due south primary source of government. The shogunates distributed land to loyal followers and these estates (shoen) were then supervised by officials such as the jito (stewards) and shugo (constables). Unlike in European feudalism, these often hereditary officials, at to the lowest degree initially, did non own land themselves. However, over time, the jito and shugo, operating far from the primal authorities, gained more and more than powers with many of them becoming large landowners (daimyo) in their own right and, with their own private armies, they challenged the authorisation of the shogunate governments. Feudalism as a nation-wide system thus bankrupt down, even if the lord-vassal relationship did go on after the medieval period in the grade of samurai offering their services to estate owners.

Azuchi Castle

Origins & Construction

Bullwork (hoken seido), that is the organisation between lords and vassals where the onetime gave favour or on (e.grand. land, titles, or prestigious offices) in exchange for armed services service (giri) from the latter, began to be widespread in Japan from the beginning of the Kamakura Menses (1185-1333 CE). The main instigator was Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147-1199 CE) who had established himself every bit the armed services dictator or shogun of Japan in 1192 CE. Replacing the authorization of the Japanese Emperor and the regal courtroom, the new system saw Yoritomo distribute land (which was often confiscated from defeated rivals) to his loyal followers and allies in return for their military service and connected support. Yoritomo was peculiarly adept at enticing members of the rival Taira association to his, the Minamoto cause by offering them land and positions if they agreed to exist his vassals in the new club.

The system immune the shogun to have straight control of most of his territory, but the lack of formal institutions of government would be a lasting weakness.

Unlike in Europe, the feudal system of Nippon was less contractually based and a much more than personal matter betwixt lords and vassals with a potent paternalistic influence coming from the one-time, who were frequently referred to as oya or 'parent.' This 'family' experience was farther strengthened by the fact that many lord-vassal relationships were inherited. The system allowed the shogun to take direct control of nearly of his territory, but the lack of formal institutions of government would be a lasting weakness of the shogunates as personal loyalties were rarely passed on to successive generations.

Jito

Some of the loyal followers of the shogun received many estates (shoen), which were frequently geographically disparate or distant from their traditional family homes, and so, rather than manage them directly themselves, they employed the services of an appointed steward (jito) for that purpose. Jito (and shugo - see below) was not a new position but had been used on a smaller calibration in the Heian Period (794-1185 CE) and, appointed by the shogunate government, they became a useful tool for managing country, taxes and produce far from the capital. Here, likewise, is another departure with European bullwork as stewards never (officially) owned state themselves, that is until the wheels started to come up off the feudal system.

Jito literally ways 'head of the country', and the position was open to men and women in the early on medieval menstruation. Their chief responsibility was to manage the peasants who worked their employer'due south land and collect the relevant local taxes. The steward was entitled to fees (about ten% of the state'due south produce) and tenure just was often leap by local customs and also held answerable to such national law codes as the Goseibai Shikimoku (1232 CE). In improver, aggrieved landowners and vassals could, from 1184 CE, turn to the Monchujo (Board of Inquiry) which looked afterward all legal matters including lawsuits, appeals, and disputes over land rights and loans. In 1249 CE a Loftier Court, the Hikitsukeshu, was formed which was specially concerned with whatsoever disputes related to state and taxes.

Minamoto no Yoritomo Painted Wall-hanging

Many jito eventually became powerful in their own right, and their descendants became daimyo or influential feudal landowners from the 14th century CE onwards. These daimyo ruled with a large degree of autonomy, even if they did have to follow sure rules laid downwards past the government such every bit where to build a castle.

Shugo

Another layer of estate managers was the shugo or military machine governor or constable who had policing and administrative responsibilities in their particular province. In the 14th century CE, at that place were 57 such provinces and so a shugo was involved in several estates at one time, unlike the jito who only had one to worry well-nigh one. A shugo, literally significant 'protector', made decisions co-ordinate to local customs and military laws and, similar the jito, they collected regular taxes in kind for the shogunate government, a portion of which they were entitled to keep for themselves. They were also charged with collecting special taxes (tansen) for one-off events similar coronations and temple-building projects and organising labour for land projects similar building roads and guesthouses forth the routes. Other responsibilities included capturing pirates, punishing traitors, and calling upward warriors for use by the state - non simply in wartime but also equally part of the regular rotation system where provinces supplied guards for the upper-case letter Heiankyo (Kyoto).

By the 14th century CE, the shugo had as well assumed the responsibilities of those jito who had not become daimyo.

Over time the position of shugo became, in effect, one of a regional governor. The shugo became ever more powerful, with taxes existence directed into their own pockets and such rights as collecting the tansen oftentimes existence given to subordinates as a way to create an alternative lord-vassal relationship without whatever land substitution being involved. The giving out of titles and organising private arrangements with samurai also allowed the shugo to build up their own personal armies. Following the failed Mongol invasions of Japan in 1274 and 1281 CE, shugo were legally obliged to reside in the province which they administered for greater land security, but whether this was always carried out in practice is unclear. By the 14th century CE, the shugo had also assumed the responsibilities of those jito who had not go daimyo, and past the 15th century CE, nearly shugo inherited the position.

Weaknesses of the Organisation

One of the bug for the jito and shugo was that their authority out in the provinces, far from the primal regime, often relied on the goodwill of the locals, and when the shogunate government was weak - as information technology ofttimes was - samurai warriors and ambitious landowners ofttimes ignored demands for taxes or fifty-fifty took matters into their own hands and overturned the established arrangements of lord and vassal to increase their own ability and wealth.

An additional weakness in the system was that jito and shugo depended entirely on local sources for their income, not the cardinal authorities and this meant that they often made entirely self-interested arrangements. Thus, the shogunate itself became a largely irrelevant and invisible establishment at a local level. Farmers oft made private deals with officials, giving, for example, a small parcel of state in exchange for a delay in payment of taxes or a negotiated percentage in order to pay their expected fees annually. As a upshot, the whole setup of land buying in Japan became very complex indeed with multiple possible landowners for any stretch of land: private individuals (vassal and not-vassals), regime officials, religious institutions, the shogunate, and the Crown.

Yet some other problem was that when jito inherited from their fathers there was often non enough money to make a living if the rights of income had to exist distributed among several siblings. This situation led to many jito getting into debt as they mortgaged their right of income from a given estate. There were additional weaknesses to the feudal organisation as time wore on, besides, namely the difficulty in finding new land and titles to award vassals in an era of stable regime.

In the Sengoku Catamenia or Warring States Period (1467-1568 CE) Japan suffered from constant civil wars between the rival daimyo warlords with their ain private armies who knew they could ignore the shugo and other officials of the government which was now impotent to enforce its volition in the provinces. Land was too ending up in fewer and fewer hands equally the daimyo with almost armed forces might swallowed up their smaller rivals. By the Edo Menses (1603-1868 CE) there would be a mere 250 daimyo across the whole of Japan. The phenomenon of new rulers overthrowing the established order and of branch families taking the estates of the traditional major clans became known as gekokujo or 'those below overthrowing those higher up.'

The effect of this social and administrative upheaval was that Nippon was no longer a unified state merely had go a patchwork of feudal estates centred around private castles and fortified mansions equally loyalties became highly localised. Villages and pocket-sized towns, largely abased by the authorities, were obliged to class their ain councils (and so) and leagues of common aid (ikki). Non until Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582 CE), who defeated his rival warlords in the central part of the archipelago in the 1560s CE, did Japan begin to await similar a unified state once again.

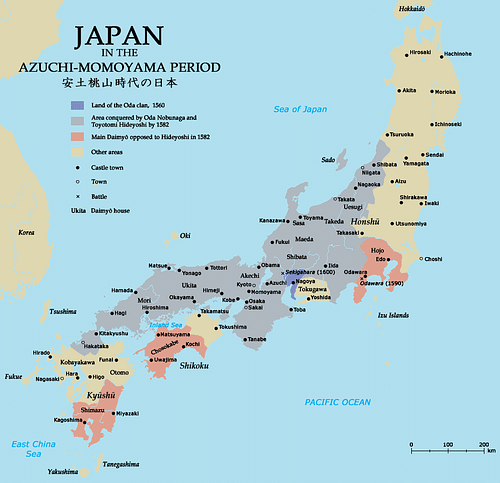

Map of Nihon in the 16th Century CE

With the inflow of the much stronger Tokugawa Shogunate (1603-1868 CE) the daimyo were finally put in their place and severe restrictions imposed on them. These included a ban on moving their troops exterior of their area and not existence able to brand political alliances in their own name, build more one castle, or ally without the shogun'due south blessing. The feudal organization did, nevertheless, continue in the guise of samurai swearing loyalty to their particular daimyo up to the Meiji Menses (1868-1912 CE), even if at that place was now a prolonged period of relative peace and military machine service was less needed than in medieval times.

From the 17th century CE, and then, the Japanese feudal system was, instead of existence a nation-wide pyramid structure of land distribution, largely one of local samurai warriors offering their services to a big estate owner or warlord in exchange for use of state, rice, or cash. Information technology is for this reason that the bushido or samurai warrior lawmaking was developed which aimed to ensure samurai remained disciplined and loyal to their employers. Meanwhile, increasing urbanisation as people moved from rural life into the cities with their greater employment opportunities, and the ever-rise number of those involved in merchandise and commerce meant that the old feudal system was applicable to fewer and fewer people as Japan moved into the modern era.

This content was fabricated possible with generous support from the Great Uk Sasakawa Foundation.

This commodity has been reviewed for accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1438/feudalism-in-medieval-japan/

0 Response to "The Samurai in Feudal Japan Were Similar to What Social Class in Feudal Europe?"

Post a Comment